Do I Live in a News Desert?

It's not a desert, but we're in a drought. A look at what's lost when local news outlets retreat from our towns.

The other day, my wife, Tracy, and I were talking about just how much road construction was happening around our neighborhood in Elkins Park. It feels like every other block is closed, rerouted, or waiting to be repaved—but we couldn’t figure out when any of it would end. Or why it all seemed to be happening at once. Or where to even look for a reliable update.

Facebook groups offered some bits and pieces. But not the full picture. Not the kind of reporting that ties things together.

And that got me wondering: Do we live in a news desert?

We live in a diverse and relatively affluent community in Montgomery County, just outside Philadelphia. It’s got leafy streets, historic homes, good schools—and, I assumed, access to solid local news. But then I stopped to ask: How would I know for sure?

I turned to the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media at UNC, where Penelope Muse Abernathy—who helped popularize the term “news desert” back in 2016—offers this definition:

“A community, either rural or urban, with limited access to the sort of credible and comprehensive news and information that feeds democracy at the grassroots level.”

Then I looked up what a literal desert is. According to National Geographic, it’s not an area with zero rainfall—it’s one with very little precipitation. Less than 10 inches per year.

So a news desert doesn’t mean no coverage. It means very little coverage.

Okay. I can work with that.

So What’s the Forecast in Elkins Park?

Technically, our community is covered. We’re within the reach of Philadelphia’s four major TV news stations, one daily newspaper, three PBS affiliates, two NPR stations, and several radio and online outlets.

But “covered” is doing a lot of work there.

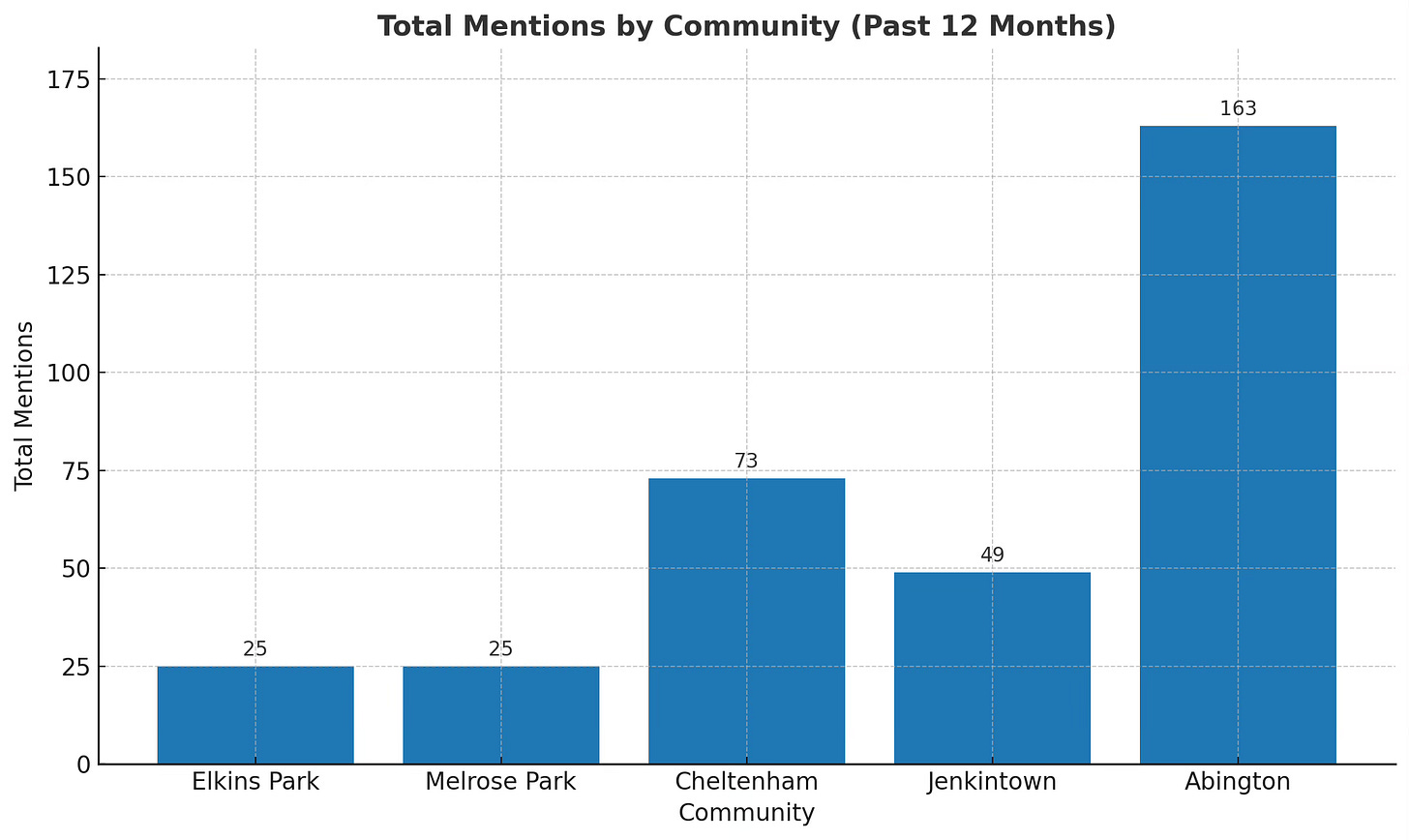

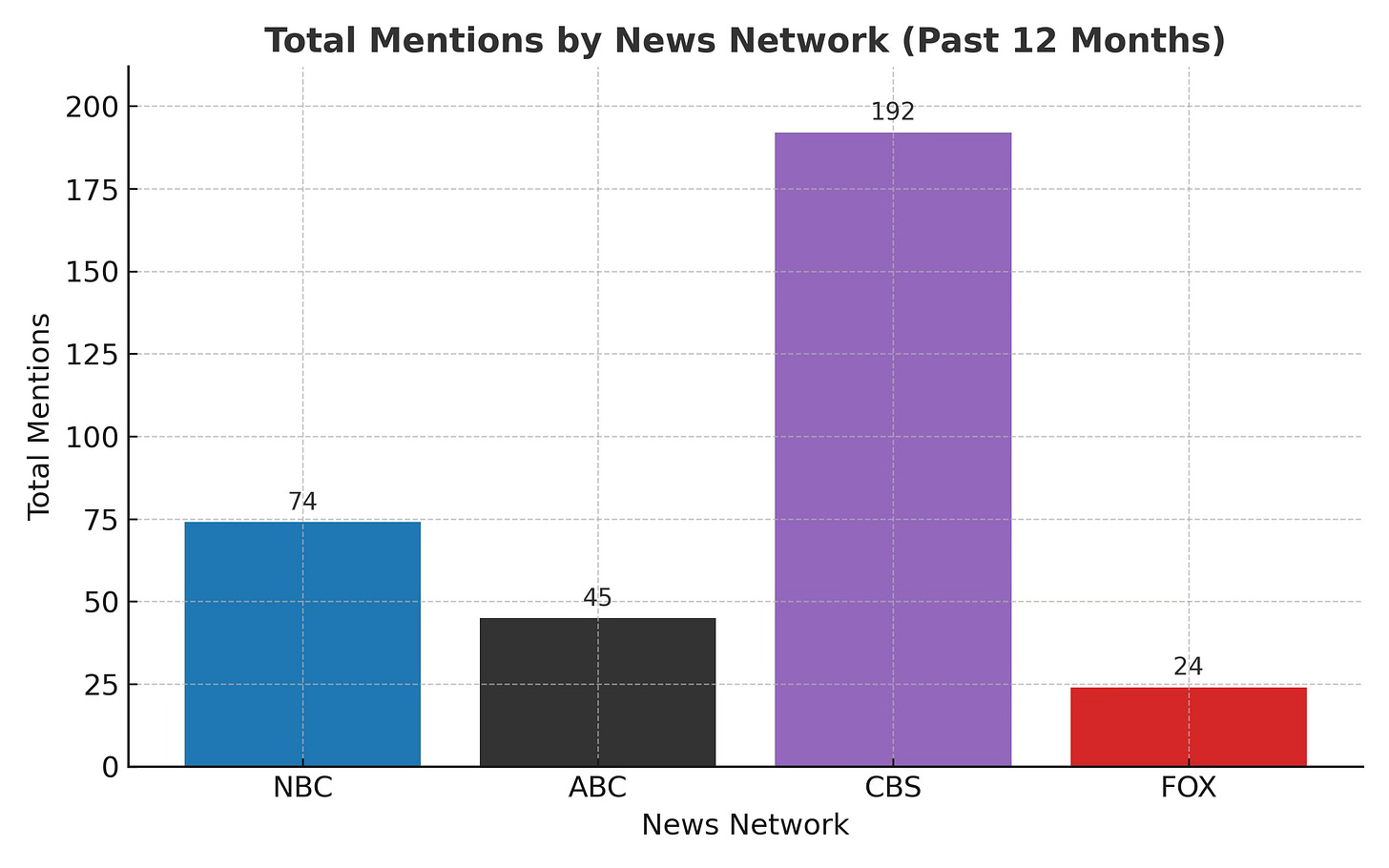

I ran a simple experiment: I searched each local TV news website for a handful of local community names—Elkins Park, Melrose Park, Cheltenham, Jenkintown, and Abington—to see how often they’ve been mentioned over the past year.

Here’s what I found:

These charts show how little we're being covered and by whom. But looking closer at the actual stories reveals something more important. My review of the articles was anecdotal, but a clear pattern emerged: the vast majority of coverage is event-driven.

The Abington numbers, for instance, are inflated by a single industrial fire at SPS Technologies that made regional news. Strip that one major event out, and the day-to-day coverage is just as thin as in the surrounding towns. This proves the point: coverage is sporadic and reactive, not proactive.

So yes, if I sat across from a local news director, they could rightly say, “See? We do cover your area.” But the numbers only tell part of the story. Because the more important question is this:

Is the coverage we do get the coverage we actually need?

What Gets Reported—And What Doesn’t

Most major outlets only show up when something blows up—literally or figuratively. Crime, a fire, a development fight. That’s the bar. Just this week, I saw a Facebook post about a possible new commercial development nearby—and one of the first comments was, “Is this real?”

A few years ago, that question might have been answered by the Inquirer or a local TV station. Today? Crickets.

This isn't just a feeling; it’s the result of a documented, strategic retreat from communities like mine. The shift began years ago. As far back as 2007, a New York Times article noted the Inquirer's new leadership had 'pulled back from the heavily local news coverage it once provided, down to the township level.'

More recently, even a direct attempt to fix the problem was reversed. In 2021, the Inquirer established a Community News Desk, which Poynter.org reported was specifically designed to cover 'underserved communities.' But earlier this year, that desk was dissolved and its eight reporters were laid off.

Meanwhile, local TV newsrooms are stretched impossibly thin, with a single reporter often responsible for covering multiple counties. When you’re tasked with covering that much ground, you can only stop for the fires and major crime scenes. The machinery of local life—the zoning meetings, the school board votes, the road construction plans—inevitably falls by the wayside.

So the vacuum that gets filled by rumor, social posts, and comment-thread sleuthing isn't accidental; it's a direct consequence of these decisions.

Desert? Drought? Something In Between?

So no, it’s not a desert. But it is parched—especially when it comes to the kind of news that helps people make smart, everyday decisions. It makes me wonder if all the focus on news deserts—important, don’t get me wrong—misses what’s happening in communities that don’t qualify as deserts but still fall through the cracks.

This leaves communities like Elkins Park in a precarious information drought. If the legacy business models can no longer support this kind of essential coverage, what new models can? Is the answer a nonprofit newsroom, a hyperlocal Substack, a citizen journalism project, or something else entirely? This is the gap where mission must meet money, and it's the central question we'll be exploring in this series.

I’d love to hear from you: Do you feel well-served by your local news, or are you living in a "news drought," too? Let me know.