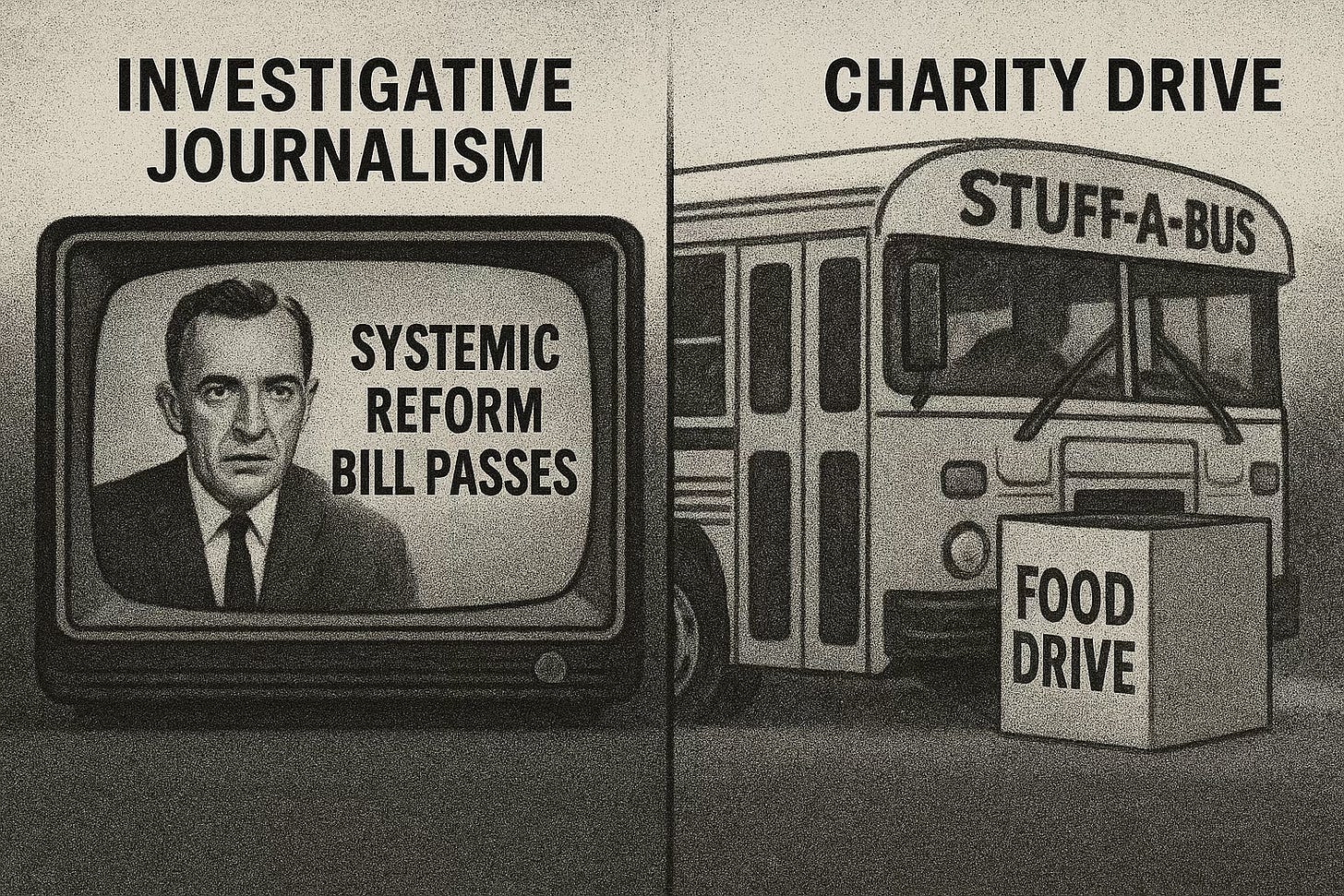

The 6 O’Clock News vs. The 5 O’Clock Food Drive

Journalism used to change policy. Now it just collects cans. It's time to remember how to do both.

In less than two weeks, 42 million Americans who depend on federal food assistance stand to lose that support altogether.

The cause: the federal government shutdown.

The benefits at stake are delivered through SNAP, the largest federal anti-hunger program in the country, which you may know better by its old nickname, “food stamps.”

Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America, told NPR in stark terms:

“If the SNAP program shuts down, we will have the most mass hunger suffering we’ve had in America since the Great Depression.”

Here is the moment for the news industry to recall its own history. That’s been getting harder to do. As the industry has been hollowed out by layoffs, it has been losing the institutional memory of its own power.

I mean the power to do more than report a crisis. Power to end one.

The news industry has for decades been organizing hunger relief through churches, pantries, and food banks. What’s changed is the form of the involvement.

When Journalism Changed Policy

The most consequential first step for years was not food drives. It was investigative reporting that led to real policy change.

In 1968, CBS broadcast its documentary Hunger in America, reported by Charles Kuralt, revealing deep malnutrition across the country. The program was a turning point. It shocked viewers. The documentary’s impact was so profound that Senator George McGovern took the Senate floor the next day. He proposed a resolution that became the basis for federal school lunch programs and the expansion of food stamps.

This came after Edward R. Murrow’s 1960 Harvest of Shame, about migrant farmworkers. CBS was strategic about its timing with that one, airing it the day after Thanksgiving.

Both documentaries took hunger off the pages and onto the screens of American homes. And viewers responded with direct action. People mailed food, money, and letters to Congress demanding policy reforms.

By 1979, doctors were testifying that severe hunger had been “virtually eliminated” from rural areas and urban slums. Infant mortality dropped by a third. Most of the credit went to the federal food programs that emerged from this media-fueled awareness campaign.

The Rise of the Food Drive

News station food drives took off in the 1980s and 1990s as a local way for stations to make a more tangible impact on their communities. These campaigns became professionalized—multi-year commitments with specific goals, coordinated between stations and branded as annual community events.

NBC 4 New York’s Feeding Our Families has generated more than 5 million meals since 2017.

Boston’s WCVB-TV partnered with the Greater Boston Food Bank during the pandemic for its Project CommUNITY: 5×5 Food Drive, raising over $3 million—enough for roughly 9 million meals.

In Los Angeles, KTLA’s long-running Take 5 to Care campaign has supported the LA Regional Food Bank for more than a decade, raising about $160,000 and 15,000 pounds of food in one of its recent drives.

The formula is familiar:

grocery-chain partnerships,

live broadcasts,

on-air talent volunteering,

and calendars timed for when food banks are running low.

The Long-Term Failure

In 1995, the United States’ food insecurity rate was 12%. In 2021, it was 10.2%.

Decades of nonstop work from food banks, food pantries, and armies of volunteers has barely moved the needle.

So if not food drives, what does work?

The very program that inspired this post: SNAP.

SNAP sends roughly nine times more food to people than the entire Feeding America network. Anti-hunger experts, even those who run food banks, will be the first to tell you SNAP is the most important tool in the toolbox.

This is the uncomfortable truth that the news industry must face.

Normalizing the Problem

Charity, as writer Andy Fisher notes:

“is easier than social change. It provides great photo-ops. It makes the donors feel good. It doesn’t get into the messiness of politics and policy.”

When news organizations frame hunger as a charity problem to be solved with canned goods, they let the systems that create hunger off the hook. They serve as a pressure-release valve for public guilt, not as a catalyst for reform.

The brutal truth is that our modern food drives have built out the very infrastructure that upholds the framework of chronic hunger.

The 1968 documentaries changed policy. Today’s campaigns mostly collect cans.

The “Both/And” Mandate for Journalism

Look, with 42 million people about to hit a benefits cliff, this is not the moment to be cynical about food drives.

They are a critical stopgap during this emergency.

Newsrooms must use their massive platforms to meet local food banks’ immediate needs.

People must eat today.

But they must, at the exact same time, remember their true power.

They must resurrect the legacy of Murrow and Kuralt.

This is the “both/and” mandate.

This means that while the “Stuff-A-Bus” drive is the 5 o’clock news, the 6 o’clock news must be an investigation.

The 5 o’clock news can cover the emergency:

“Here is where you can donate.”

The 6 o’clock news must investigate the cause:

“And here is why you have to.”

What does that 6 o’clock news look like?

“Tonight, we’re talking to the local congressional leaders whose votes led to this shutdown.”

“We’re profiling a working family who rely on SNAP and a local food pantry just to get by.”

“And we’re exploring three solutions in other states that are successfully building long-term food security, not just managing hunger.”

This isn’t theoretical.

Somewhere, in some newsroom right now, a reporter is tracing how SNAP work requirements or a federal shutdown will hit real families.

That story will shape public understanding.

Maybe even policy.

That’s what the 6 o’clock news can do — when we decide to do it.

Collecting cans is community service.

Asking why we have to, in the wealthiest country on earth, is journalism.

Right now, 42 million people need more than one thing.

They need our cans.

And they need our questions.

They need both — today’s relief and tomorrow’s reform.

Because journalism has always had two jobs:

to meet the need in front of us,

and to challenge the system behind it.

If you’ve ever covered a food drive, volunteered at one, or questioned what role journalism should play in moments like this — I’d love to hear from you.

Where do you think the balance should be between relief and reform?

Share your perspective in the comments, or forward this piece to someone who still believes journalism can do both.

P.S. - If you found this post helpful, would you please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience?

This spreads the word and keeps me writing the types of content that you have enjoyed.