The Next Reporters Won’t Have Newsrooms to Learn In

Young journalists aren’t just entering a shrinking industry. They’re stepping into one that’s lost its compass, its credibility, and its classroom.

When I started at the North Jersey Herald News, our executive editor would often hire recent grads straight out of graduate school. For many, it was the first full-time journalism job they’d had.

You could quickly learn what had inspired them, by the way: NPR and The Atlantic and The Economist, and sometimes cable news, like CNN or MSNBC — if they had cable at all, or a TV, which wasn’t always a given.

It felt like the start of something, at the time. I didn’t know I was witnessing the end of one.

There are two problems with that memory. And the two problems multiplied, together, create a compounding crisis.

The first problem is that there are fewer places like the Herald News where young and aspiring journalists can learn their craft. The second is that trust in legacy media keeps declining — and so do the institutions those same journalists once dreamed of joining.

It’s one thing if local papers vanish but national ones still hire. It’s another if the pipeline dries up and the destinations crumble too.

What happens when both disappear at the same time?

The Pipeline Is Breaking

Newspaper newsroom jobs have been cut roughly in half since 2008. And while overall U.S. newsroom employment has fallen by about a quarter during that period, newspapers themselves are also disappearing. Since 2005, more than 3,200 U.S. print newspapers have vanished — still more than two a week.

Legacy outlets are not immune. CNN cut about 6 percent of its staff in 2025. The Los Angeles Times laid off 20 percent of its newsroom in 2024. The Washington Post used buyouts in 2023 and cut about 4 percent of its workforce in 2025, mostly outside its core newsroom.

Comcast is spinning off many NBCUniversal cable networks, including MSNBC and CNBC, into a new company called Versant.

It means fewer entry-level jobs. It means fewer veteran journalists left to mentor and train the next generation.

It’s not just a hiring crisis. It’s a credibility crisis.

Trust in mass media is at or near record lows across the board, whether you look at Gallup or Pew — about 31 percent of Americans say they trust it a great deal or fair amount — and younger adults are substantially less trusting than older ones.

Young journalists aren’t just entering an industry in financial trouble. They’re joining one their peers have largely stopped believing in.

Young People Are Voting With Their Feet

You can see the warning signs in more than newsroom budgets. You can see them in college data.

Enrollment in journalism and mass communication programs at the undergraduate level has dropped from 59,561 students to 53,665 students between 2018 and 2021, according to a national study of the field.

Even at schools where programs still exist, students are hedging their bets. The University of Minnesota’s Hubbard School is typical. One hundred fifty-one students there majored in journalism in 2023; more than double as many chose strategic communication. That’s the shift we’re seeing nationwide.

Graduate programs are struggling, too. The University of Nebraska reported a 28 percent decline in journalism graduate enrollment over the course of a year.

There was a short-lived “Trump bump” after 2016, when attacks on the press inspired a spike in applications. But that wave receded.

The long-term trend is clear: fewer people are willing to spend thousands of dollars on a college education, in part to prepare for a job that may not exist, doesn’t pay well, and no longer guarantees public respect.

It’s hard to argue with them. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 4 percent decline in reporter and journalist jobs between 2024 and 2034 and a 17 percent decline in newspaper publishing specifically. Median journalist salary lags at around $60,000, compared to nearly $70,000 for public-relations specialists.

The pipeline isn’t just narrow. It’s drying up.

What Gets Lost

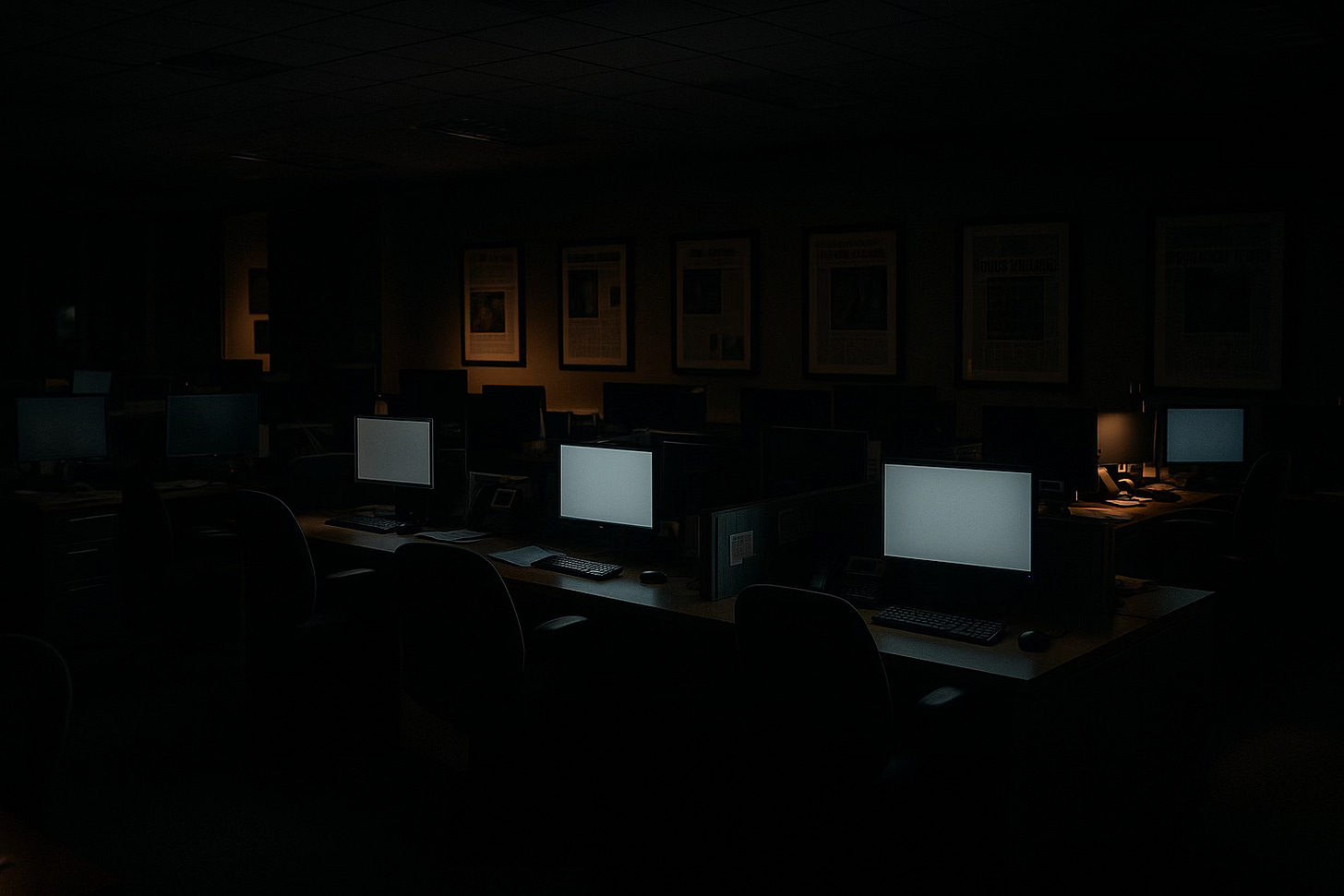

The Herald News. The Allentown Morning Call. The hundreds of small papers that once gave young reporters their start — they weren’t glamorous, but they were classrooms.

At the Herald News, we sent reporters to cover Sarajevo and the Dominican Republic, Israel and Palestine. They learned hard skills you can’t pick up in college: cultivating sources, pulling records, writing on deadline, editing in layers, reading a budget, tracking a bond referendum.

And they learned softer ones, from the veterans who coached as much as they covered their own beats.

They learned what it meant to be a journalist, not just how to write or report.

A reporter will pitch a story because it’ll get clicks. An editor asks, “But who needs to know this?”

A reporter will get one source and want to publish. The editor says, “We need two.”

Someone will write about a heated school-board meeting and let their frustration bleed into the copy. The editor crosses it out and says, “Your job isn’t to be angry. It’s to inform.”

That’s how you learn verification isn’t optional. That’s how you learn the difference between fact and opinion.

And those moments — those lessons — are what defined the boundary between journalism and content creation.

Content creation is about engagement. Journalism is about accountability. One chases attention. The other builds trust.

You learn the unspoken rules too. When to push and when to pull back. How to own a correction. Why you can’t attend a political fundraiser, even off the clock. What to do when a powerful person tries to intimidate you.

None of that’s written in a handbook. You learn it by standing next to people who’ve lived it.

Without that structure, young journalists are left to figure it out on their own. Or worse, they assume engagement is the same thing as good journalism. They confuse personal brand with public service. They publish before verifying. Not because they’re careless — but because no one ever taught them how to tell the difference.

When the North Stars Fade

I wrote earlier this year about my time as an editorial assistant at Newsday, and how working alongside Pulitzer winners like Sydney Schanberg, Murray Kempton, and Jimmy Breslin shaped everything I know about this craft.

Those bylines meant something. They carried weight. When Breslin wrote about Queens or Kempton wrote about city politics, people paid attention because both the reporter and the institution had earned their trust.

But what happens when those institutions are fading, too?

The aspiration economy has fractured. There’s no longer a shared sense of what “making it” looks like.

A young journalist can look at a New York Times reporter and see the prestige. They can also see the layoffs, the low starting pay, and the constant public attacks. Or they can see a Substack writer making six figures and think, maybe that’s the smarter path.

Maybe it is. Maybe it isn’t. The truth is, no one knows anymore.

Some are building followings on TikTok or YouTube, blending personality and reporting. Others are joining nonprofits like ProPublica or The Markup, trading stability for mission. Some are launching newsletters or podcasts. A few are still making it to the big outlets. Most are piecing together a living somewhere in between.

The old markers of prestige haven’t vanished, but they’ve lost their monopoly. A Times byline still matters, but so does a viral investigation by an independent reporter. A cable segment still builds credibility, but so does a well-crafted podcast. Influence has splintered, and no one’s quite sure how to measure it.

That creates a strange tension. Join a legacy outlet, and you get all the baggage that comes with it. Go independent, and you’re on your own — no editors, no lawyers, no safety net. Build an audience as a journalist-influencer, and you might reach more people than ever before — but at what cost?

And it doesn’t fix the old inequities. Independence favors the same people the old system did: those with safety nets and followings and marketing skills, leaving behind the people who don’t.

And what happens to the journalism that doesn’t go viral? The city-council stories. The school-board stories. The zoning stories. The quiet watchdog work that holds power accountable but doesn’t rack up shares? Those beats have almost vanished.

A few nonprofits are trying to fill the gaps, but the holes are widening.

And even for those who go independent, burnout is built into the model. Every journalist becomes their own editor, their own publisher, their own accountant. There’s no safety net when a source turns hostile or a story takes months. Independence feels freeing — until it doesn’t.

What Comes Next

So where does that leave the next generation?

Start with honesty. The old path isn’t coming back. The jobs, the mentorship, the clear ladders — they’re mostly gone. But the work still matters.

If you’re starting out, build skills wherever you can. Find mentors in pieces, even if you have to cobble together your own support network. Learn how to verify, how to ask questions that matter, how to build trust. Don’t buy the myth that independence equals freedom without cost.

If you run a newsroom, a journalism school, or a nonprofit, stop pretending we’re going back to the old model. Invest in training. Invest in mentorship. Teach sustainability and ethics in the independent era.

If we want young people to join this industry, we need to show them a future they can actually believe in.

Because maybe the question isn’t how to save journalism. Maybe it’s how to rebuild it from what’s left.

That work is already happening, in small newsrooms, in collaborations, in nonprofits, in networks of journalists pooling what little they have to keep reporting alive.

The work still matters. The public still needs it. The path has never been less clear.

But that’s the challenge of our time: to help the next generation find their way, even without the newsrooms that once showed us ours.

If this piece resonated with you, share it with someone who still believes journalism matters. The next generation is watching — and what we do now will shape what they inherit.

P.S. - If you found this post helpful, would you please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience?

This spreads the word and keeps me writing the types of content that you have enjoyed.